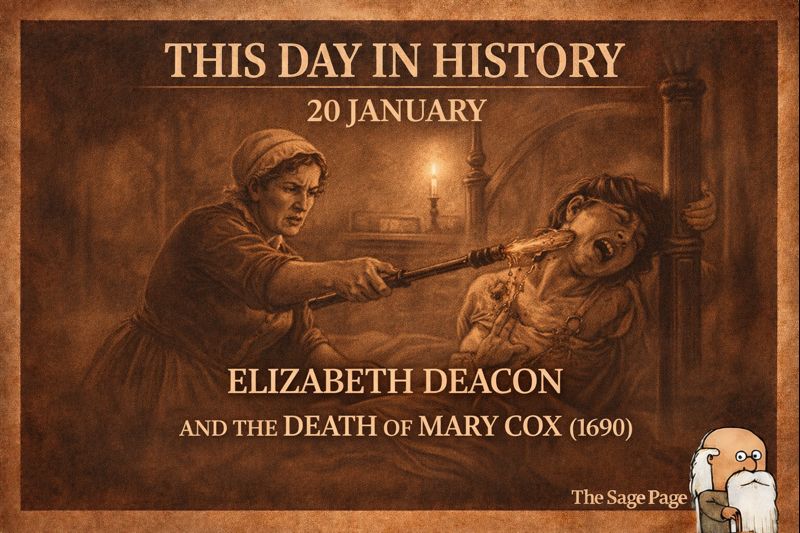

On Monday 20 January 1690, events unfolded inside a household in St Michael Wood Street that would later be exposed as one of the most prolonged and brutal cases of domestic cruelty heard at the Old Bailey.

Elizabeth Deacon, wife of Francis Deacon, a whipmaker, was tried for the wilful murder of her servant maid, Mary Cox, a girl of about seventeen years of age.

The beginnings of suspicion

The chain of violence began when Deacon discovered that Mary Cox had a shilling in her possession. Demanding to know how she came by it, the girl explained that she had received sixpence from Mrs Baker and sixpence from Susannah Middleton.

Her mistress did not believe her.

On that same Monday, Deacon ordered the girl to be tied to the bedpost and whipped severely. Two apprentice witnesses — Edward Newhall and Thomas Albrook — later testified to what followed.

Escalation

When the maid later denied wrongdoing, Deacon’s anger intensified. She struck her servant two or three times with a whip, then commanded that she be tied again and beaten so violently that the girl cried out “Murder.”

To silence her, Deacon covered the girl’s mouth with her hand.

The cruelty did not end there.

On the following Saturday, Deacon bound Mary Cox by the neck and heels, tied her once more to the bedpost, and burned her neck, shoulders, and back with a fire poker. She then struck her on the head with a hammer, forcing her to confess to being involved with thieves who supposedly planned to rob her master’s house during Bristol Fair.

The next Monday — the day before the girl died — Deacon took her servant before a Justice of the Peace, where the same confession was repeated under the shadow of violence already inflicted.

Neglect and death

After this, Deacon showed no pity.

When Mary Cox became seriously ill, she was denied food, comfort, and care. Witnesses heard her mistress say:

“Hang her, hang her.”

She claimed the girl had the pox, and refused to provide assistance, asking, “Who can do any thing for such a wretch?”

A surgeon later testified that the wounds and stripes contributed directly to her death, alongside illness brought on by previous weakness.

Mary Cox died shortly afterwards.

The defence

At trial, Elizabeth Deacon attempted to extenuate her crime, alleging that the maid was dishonest, obstinate, and associated with thieves. She claimed the punishment was for opening her dressing box.

She produced witnesses who spoke favourably of her upbringing, but none could contradict the overwhelming testimony of violence.

One witness suggested the girl had complained of stomach pains and headaches before the beatings, or that she had made herself ill by eating ice cakes and apples, but the jury found these explanations meaningless in light of the evidence.

Verdict and sentence

The jury returned a clear verdict:

Guilty of wilful murder.

Elizabeth Deacon was sentenced to death.

However, the sentence was respited, as she was found to be pregnant — a legal provision that delayed execution but did not overturn the conviction.

Why this case matters

This case exposes the extreme vulnerability of servants in early modern London, particularly young women living under absolute household authority.

It also demonstrates:

- the weight given to apprentice testimony,

- the court’s recognition of sustained cruelty, not just fatal blows,

- and the limits of maternal reprieve within capital punishment.

For Mary Cox, 20 January 1690 marked the beginning of a suffering that would soon end her life.

For Elizabeth Deacon, it marked the moment private brutality became public crime.

Source

- Elizabeth Deacon, Old Bailey Proceedings, 26 January 1690, offence dated 20 January, case ref t16900226-1.

Thank you for reading my writings. If you’d like to, you can buy me a coffee for just £1 and I will think of you while writing my next post! Just hit the link below…. (thanks in advance)