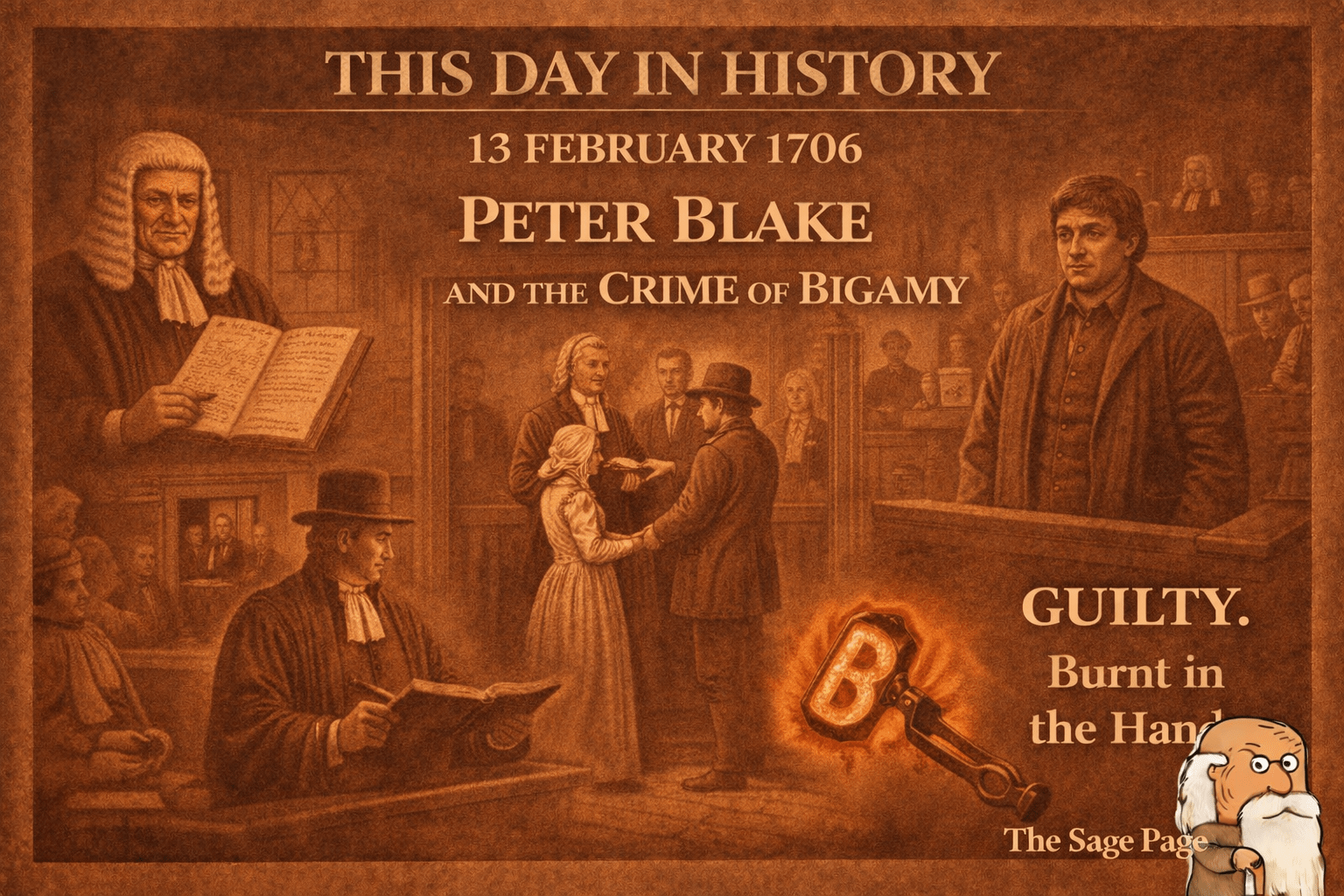

On 13 February 1706, in the parish of St. Martin’s, New Sarum (Salisbury), Peter Blake married Mary Blackstone.

Sixteen years later, that marriage returned to haunt him.

In October 1722, Blake stood before the Old Bailey indicted for taking a second wife while his first was still living — the serious felony of bigamy.

He was found guilty.

The First Marriage

Thomas Holms, Clerk of St. Martin’s Parish in New Sarum, gave clear evidence:

“The Prisoner on the Thirteenth of February 1706 was married to Mary Blackstone Spinster, of the same Parish.”

Holms confirmed he had seen Mary Blackstone alive within three weeks of giving testimony. He even produced the parish register to verify the marriage.

The prosecution strengthened its case further: Edward Farr travelled to Salisbury to obtain certification of the first marriage and saw Mary Blackstone there — living, and with three children by Blake.

The first marriage was not in doubt.

The Second Marriage

Despite that existing union, Blake married again.

Mary Blake testified that on 31 August 1722 she was married to him at St. Peter’s, Cornhill, by licence from the Archbishop’s Court.

She had known him only briefly:

“Having seen him but the Wednesday before.”

They cohabited for three nights. Then she heard rumours.

She was told he had another wife.

She went to him no more.

The officiating minister, Mr. Swan, produced the licence. The parish clerk confirmed the ceremony.

The second marriage, too, was not in doubt.

The Defence

Blake claimed he believed his first wife to be dead.

“He had heard by several Letters that his first Wife was dead, and thought that she was.”

He further alleged interference by one Mr. Clifton, suggesting jealousy and financial motives had stirred the inquiry against him.

But belief is not proof.

And the parish register was a stubborn witness.

The Verdict

The jury returned their decision:

Guilty.

Bigamy in the early eighteenth century was not a mere domestic irregularity. It was a felony, carrying serious penal consequences.

Sentence

On 10 October 1722, when judgment was pronounced, Peter Blake was among those:

Burnt in the Hand.

Branding was a common punishment for certain felonies at this period. A hot iron, often marked with a letter corresponding to the offence, was pressed against the offender’s thumb.

The mark served as:

- A public sign of conviction

- A deterrent

- A permanent legal record on the body

Branding spared Blake from harsher penalties such as death or transportation, but it left him marked — physically and socially.

(For context on branding as punishment, see the Old Bailey’s overview of penal practices in the early eighteenth century.)

Why This Case Matters

The case of Peter Blake reveals:

- The legal seriousness of marriage law in early 18th-century England

- The importance of parish registers as documentary evidence

- The global and local mobility of working people

- The use of branding as a judicial punishment

Unlike the petty theft cases of February 1818 and 1819, this was a moral and legal breach touching the sanctity of marriage itself.

And though he escaped the gallows, Blake left the courtroom permanently marked.

Sources

- Old Bailey Proceedings, October 1722 session, trial of Peter Blake (t17221010-19)

- Old Bailey Online, “Punishments at the Old Bailey” — branding

Thank you for reading my writings. If you’d like to, you can buy me a coffee for just £1 and I will think of you while writing my next post! Just hit the link below…. (thanks in advance)