The Auction Mart Shooting: Jealousy, Scandal and Transportation

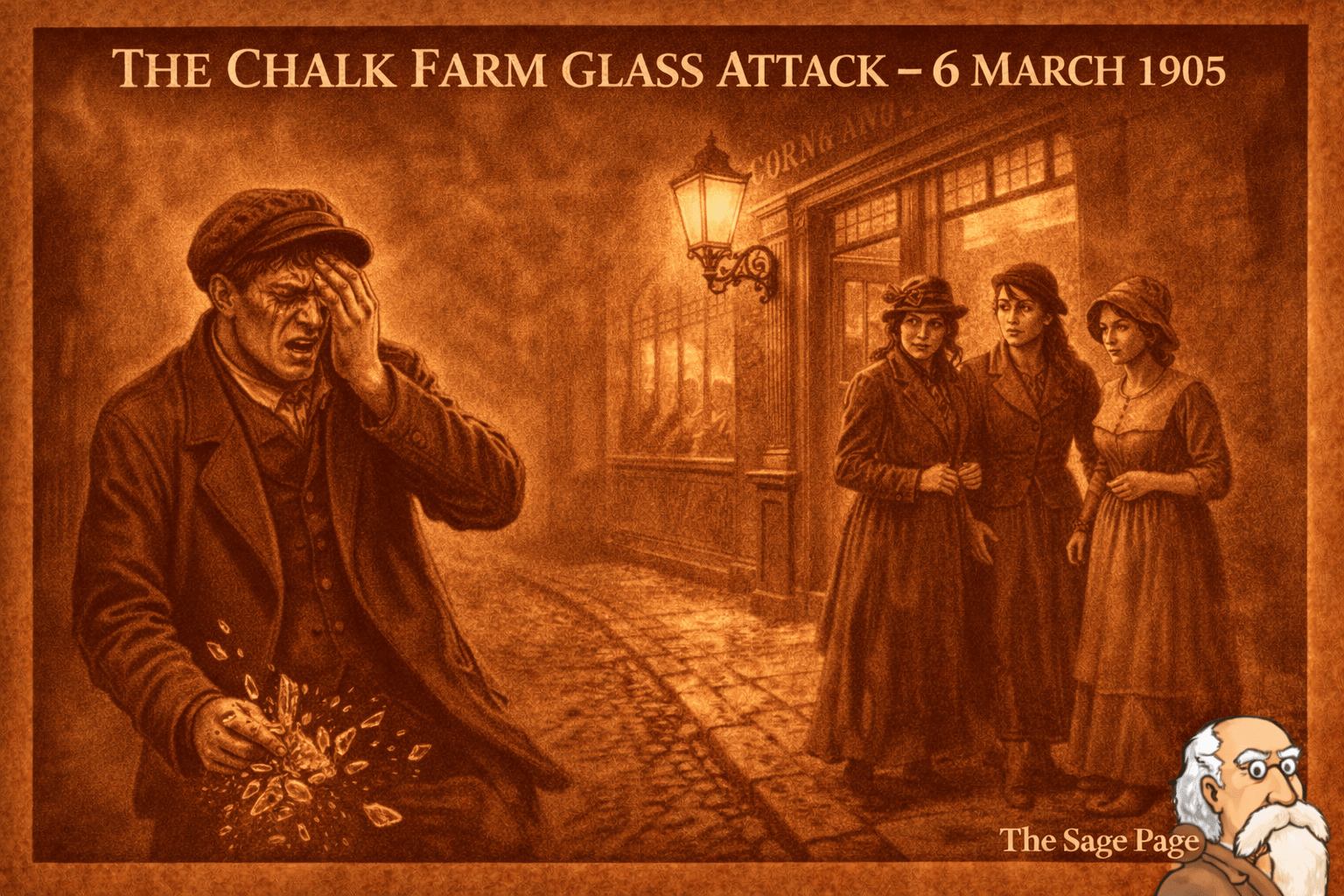

On the night of 12 December 1842, beneath the gaslight of Bartholomew Lane, a young potman named William Cannell, aged just twenty-one, shot the upper barmaid of the Auction Mart Hotel in the back at point-blank range.

He then cut his own throat.

And yet — she lived.

And he did too.

By February 1843, London was riveted.

The Setting: The Auction Mart Hotel

Behind the bustling commercial rooms of the Auction Mart stood its tap and hotel — a busy, respectable establishment.

Elizabeth Sarah Magness, forty years old and married (though posing as a widow), managed the lower bar. Cannell worked beneath her as potman.

Theirs was a relationship that hovered uneasily between flirtation and friction.

A Tangle of Improper Familiarities

Cannell had:

- Attempted to kiss her repeatedly

- Once succeeded

- Been discovered (or alleged to have been discovered) hiding in the women’s bedroom

- Expressed emotional fixation

- Told another servant: “I wish I was in heaven, and Mrs. Magness was with me.”

Meanwhile:

- She had scolded him publicly

- Called him a “forward vagabond” and later a “beggarly wretch”

- Rebuked his attentions

- Denied any impropriety

Rumours circulated among the staff.

Reputations trembled.

Victorian workplaces were tinderboxes of proximity, hierarchy and gossip.

The Night of the Shooting

Shortly before midnight:

- Mrs. Magness went to lock the outer gate.

- Cannell followed her.

- In a dim corridor she felt his hands on her shoulders.

- She pushed him away.

Then —

Click.

Bang.

A pistol shot rang through the passage.

She collapsed, shot through the ribs, the ball passing near her heart.

He cried:

“Woman! what have I done?”

Moments later, armed with a bloodied knife, he reportedly said:

“Now I’ll finish you.”

She fled upstairs screaming “Murder!”

He cut his own throat.

The Medical Reality

The surgeon testified:

- The bullet entered near the eighth rib.

- It exited near the sixth rib.

- The lungs were likely perforated.

- She was in imminent danger for days.

Amazingly, she survived.

Cannell’s throat wound was serious but not fatal.

The Bedroom Incident

Weeks before the shooting, Cannell had allegedly climbed through a window into the women’s sleeping quarters.

His explanation?

He climbed in “as a joke” to watch them get into bed… fell asleep… and hid under the bed when discovered.

Victorian juries would have read between the lines.

This prior scandal formed the emotional backdrop to the shooting.

Intent — Murder or Passion?

The indictment included:

- Intent to murder

- Intent to maim

- Intent to do grievous bodily harm

The jury convicted him only on the fourth count.

They strongly recommended mercy.

Why?

- Youth (21)

- Good character testimony

- Emotional agitation

- Apparent remorse

- Attempted suicide immediately after

The law could be stern — but juries often softened it.

Sentence

Instead of execution, Cannell received:

Transportation for Fifteen Years

Convict Ship: Emerald Isle

Departed: 30 June 1843, Sheerness

Arrived: 12 October 1843, Hobart

Van Diemen’s Land awaited him.

Epilogue: A New Life in Tasmania

Remarkably:

- Cannell survived transportation.

- On 10 November 1851, he married Parthena Emma Eugenia Eldershaw in Hobart.

- He received a Conditional Pardon on 2 September 1851.

From jealous London potman to transported convict to pardoned colonial settler.

A life that might have ended on the gallows instead continued beneath Southern skies.

Themes for Reflection

This case touches on:

- Workplace intimacy in Victorian service

- Reputation and female respectability

- Male possessiveness

- The emotional volatility of youth

- Jury mercy

- The empire as a penal escape valve

And above all —

The fragile boundary between flirtation and violence.

Sources

- Central Criminal Court (Old Bailey) Proceedings, 27 February 1843, trial of William Cannell, assault and wounding with intent (Auction Mart Hotel / Bartholomew Lane).

- Convict transportation and conduct data for William Cannell, ship Emerald Isle (departed Sheerness 30 June 1843; arrived Hobart 12 October 1843).

- Conditional Pardon record: 2 September 1851.

- Marriage record: William Cannell and Parthena Emma Eugenia Eldershaw, Hobart, 10 November 1851.

Tasmania Follow-Up Feature

From Auction Mart to Hobart: William Cannell’s Second Life

When William Cannell left England in the summer of 1843, he left behind more than a courtroom.

He left behind:

- The Auction Mart Hotel

- A shot fired in a narrow passage

- A woman’s screams in the dark

- A razor, a pistol, and a throat wound

- A London jury’s uneasy mercy

By October, he was in Hobart, on the far rim of the empire — a place that turned British punishment into geography.

The Voyage: Emerald Isle, 1843

Cannell sailed aboard the Emerald Isle, departing Sheerness on 30 June 1843, arriving at Hobart on 12 October 1843.

For transported convicts, the ship was not merely a means of travel — it was the threshold between two legal identities:

- In Britain: prisoner, stigma, past

- In Tasmania: labour, surveillance, reinvention

A fifteen-year sentence meant he was not expected to return.

Transportation was, in practice, a form of exile with paperwork.

Arrival: What Hobart Meant in 1843

By 1843, Van Diemen’s Land was no longer an experimental colony. It was a mature penal system:

- Established assignment networks

- Settler demand for labour

- Strict discipline and record-keeping

- A social world where conviction followed a person like a shadow

Men like Cannell were valuable, but controlled.

The colony wanted strong bodies and steady hands — but it kept a close eye on them.

Life Under Sentence

A transported convict’s world was built from permissions and restrictions.

Everything mattered:

- Where you could live

- Whom you could work for

- Whether you could move

- Whether you could marry

- Whether you could own property

- Whether your past would be forgiven, formally or informally

Even when a man behaved well, freedom came in stages.

Not as a door, but as a series of gates.

Conditional Pardon: Freedom, With Strings

On 2 September 1851, Cannell received a Conditional Pardon.

A conditional pardon was not full freedom. It typically meant:

- You were no longer under daily penal control

- But you could not legally return to Britain

- Your liberty remained geographically bounded

It was the state saying:

“You may live — but not where you began.”

Permission to Marry — and a New Name in the Records

Only weeks after the pardon, Cannell secured permission to marry.

On 10 November 1851, in Hobart, he married:

Parthena Emma Eugenia Eldershaw

That detail is quietly extraordinary.

Transportation often shattered family possibilities. Many convicts lived hard, temporary lives at the edge of the settlement.

Marriage suggests:

- stability

- accepted standing (or at least tolerated)

- a future that extended beyond mere survival

Whatever Cannell had been in Bartholomew Lane, he was now a man who could appear in a church record as a husband.

The Great Victorian Irony

Cannell’s crime was born from a refusal to accept limits:

a woman’s rejection, a bruised pride, a spiralling obsession.

Tasmania’s penal system was built on limits.

It trained men in boundaries:

- where you may go

- what you may do

- who you may speak to

- what you may hope for

If the empire was Britain’s punishment machine, it was also — sometimes — a brutal form of rehabilitation.

Not gentle.

Not kind.

But transformative.

A Thought for Elizabeth Sarah Magness

Cannell’s colonial record is traceable: ship, pardon, marriage.

Elizabeth Sarah Magness’s later life is harder to follow — as is so often the case.

Yet it is her survival that makes Cannell’s second life possible.

The story’s hinge is not the shot.

It is that she lived.

Why This Follow-Up Matters

This companion story shows the full Victorian arc:

- A London crime of passion

- A jury’s mercy

- The empire as sentencing infrastructure

- A transported man becoming, on paper, respectable

It is easy to imagine transportation as simply “removal.”

In reality, it was a violent form of social engineering — turning offenders into settlers, and punishment into population.

Conditional Pardons Explained

Freedom — But Not Home

When Victorian judges sentenced a criminal to transportation, they did not simply banish them. They inserted them into a carefully structured system of graduated freedom.

One of the most misunderstood stages in that system was the Conditional Pardon.

William Cannell received one in September 1851 — eight years after arriving in Hobart.

But what did that actually mean?

What Is a Conditional Pardon?

A Conditional Pardon released a transported convict from most penal restrictions — on condition that they did not return to Britain or Ireland.

It was freedom with geography attached.

You were:

- No longer assigned to a master

- No longer under daily convict discipline

- Allowed to work, marry, own property

- Recognised legally as free within the colony

But:

- You could not legally return to the United Kingdom

- You remained barred from “home” for the duration of your original sentence

- In some cases, permanently

The empire had removed you.

The empire would not easily let you back.

The Ladder of Freedom in Tasmania

Transportation was not a single punishment. It was a process.

A typical progression might include:

- Assignment – Labour under a settler or government authority

- Ticket of Leave – Limited freedom within a district

- Conditional Pardon – Broader liberty within the colony

- Absolute Pardon – Full restoration of civil rights (rare, and often late)

Each stage required:

- Good conduct

- Recommendations

- Administrative approval

Freedom was earned bureaucratically.

Why Grant Conditional Pardons?

Conditional pardons served several purposes:

1️⃣ Labour Retention

The colony needed workers.

A pardoned man was more stable — more likely to settle, farm, trade, and remain useful.

2️⃣ Behavioural Incentive

Good conduct could be rewarded.

Punishment had a visible ladder.

3️⃣ Imperial Strategy

Britain solved two problems at once:

- Removed offenders

- Populated colonies

Transportation was social engineering disguised as sentencing.

What It Meant in Real Life

For someone like Cannell, a conditional pardon meant:

- He could marry (which he did, within weeks)

- He could establish a household

- He could move socially from “convict” toward “settler”

- He could build a future

But it also meant:

- England was closed to him

- The life before 1843 was legally severed

A conditional pardon did not erase the crime.

It redirected the life.

The Psychological Reality

Transportation created a strange dual identity:

- Legally free

- Socially marked

Convicts often carried stigma for years — sometimes for life.

But in growing colonial towns like Hobart, reinvention was possible.

Distance softened memory.

Empire rewrote biography.

The Great Irony

Cannell fired a pistol in a narrow London passage in 1842.

Nine years later, he stood in a Tasmanian church and married under his own name.

The British penal system had intended to punish him.

Instead, it relocated him.

Why This Matters Today

Understanding conditional pardons helps us see transportation not as a simple act of exile, but as:

- Structured rehabilitation

- Controlled migration

- Imperial expansion policy

- And, sometimes, unintended second chances

It was harsh.

It was calculated.

And occasionally — as in Cannell’s case — it allowed a life to begin again.

Thank you for reading my writings. If you’d like to, you can buy me a coffee for just £1 and I will think of you while writing my next post! Just hit the link below…. (thanks in advance)